The problem was my father, Lenny, everyone’s favorite mailman. His presence formed a vortex—or was it more like a tornado?—shaping roiling debates issues in our extended Jewish family over the precarious question of whether we would all live or die.

My father was not your typical Jewish father, at least as far as the reigning stereotypes went. He was hardly the sort of “wise man” who my friends proudly brought to ball games and Broadways shows, the chummy fellow who might drive to another borough to pick up that chintzy cashmere sweater one’s grandmother admired from a Macy’s commercial, the guy who made sincerely funny jokes about your character that taught you a thing or two about yourself but never at your expense, in other words a true “mensch.” My father, instead, was more interested in being a type of ethnic trouble mean maker. His jokes made everyone laugh because they put you down, doing so with a swagger accompanied by a booming baritone voice that called to mind Marlon Brando in his more crass moments in a Streetcar Named Desire, bellowing our names as if we were his “Stella!” to egg us on to laugh at each other’s foolish failings.

Like Brando, or perhaps more like Bogart, he was quintessentially handsome, but also in a somewhat more menacing manner. His comely, sensual profile boasted a prominently Jewish nose and shyly pouty lips upon which his ever-present Lucky Strike dangled and then a bushel of reddish, brown tousled hair boldly resisted his receding hairline. His visage was sculpted onto of his six-foot stately stature and a head-to-toe sinewy muscularity accrued through a depression-era working class life, a “working stiff,” as he might have put the situation.

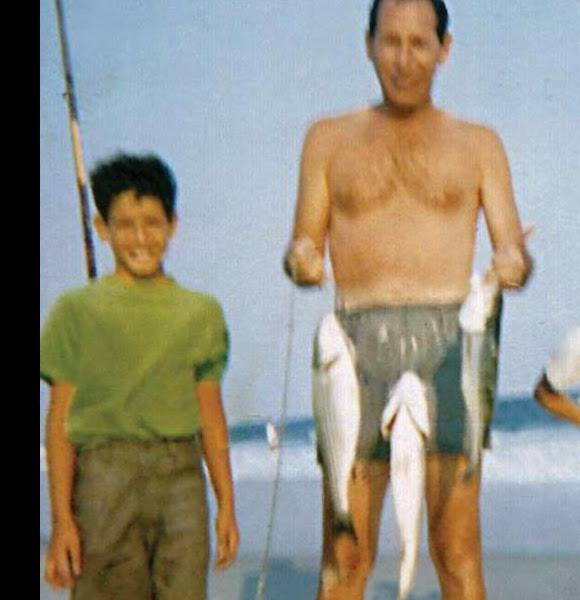

This assemblage of personality was thrown into sharp relief by a subtle sun tan that did not entirely languish even in the frigid Bronx winters. His warm skin tone was afforded him by his fisherman’s life, which he cherished almost more than alcohol during bi-monthly Sunday sojourns to Jones Beach, for which he joyfully dragged my younger brother and me at the ungodly crack of dawn no matter the season. In this way, he sought to provide the “men” of the family with marathon fishing expeditions, a kind of male bonding, if you will. Mother was happy to be on her own with her girlfriends while we “boys” went to the Long Island shore. During the Passover season, while Daniel and I were off from school, we fished several times a week, and became quite good about wading into the waves and casting our lines out to the farthest reaches of the Atlantic to our father’s grinning and drunken pride. We munched ravenously on soggy tuna-matzos sandwiches when not reeling in eight-pound sea-basses onto the shore whether rain, fog or sun in our protective rubber boots and glamorous sunglasses. I often imagined our bronze Ashkenazic visages adorning the covers of Field and Stream as that magazine could have been greatly enriched by our ethnic je ne sais quoi about which we were more than enamored.

Despite all these high marks on the masculine measuring stick, my father sadly suffered from a secret shame about being seen of as Jewish and therefore weak(ly) and unmanly. Part of the fact was that he, in fact, he preferred to be mistaken for an Irish street kid, which he did more than a little resemble. This was not without due cause. His doting mother, my grandmother, Miriam, was the proud member of that small Jewish community which settled in Dublin in the 19th Century, emigrating to the U.S. in the years before WWI. She spoke her fluent Yiddish with a sassy brogue which emerged when she had “a spot of brandy,” which was every day, while grinding the onions and white fish that, while boiling, would alchemically manifest boiling into her revered gefilte fish. A Lucky Strike might dangle from her lipsticked lips as she hummed in her hardly shy tipsiness such all-time favorites Oyfn Pripetchik and My Yiddishe Mama when she was not berating her husband, Aaron, for the alleged affairs she accused the charismatic furniture salesman of having when he slinked home at odd hours of night: “Jesus, Mary and Joseph, oy vey is mehr” this god-fearing Jewish woman would foully swear, muttering under her breath so that we wouldn’t underneath the full extent of her dirty Irish tongue because she rightly fancied herself a world class balaboosta (a Yiddish term to mean the quintessential housewife, homemaker, mother, cook and gracious hostess) “who the hella were ya snoggin? I’ll give ya a face on ya like a busted cabbage, ya talk a lot of shite!”

Miriam idealized my mother’s mother and father, Ida and Gustave, and called them respectfully by their Hebrew names, “Heicke,” and “Kiva,” and sometimes called me by my Hebrew Name, “Daveed,” after King David, my namesake, to help remind us all that our Sadownick clan derived from the Priestly (or Kohen class) since Biblical days, whereas my mother’s Levine class, were mere “Levites,” which meant that they played music and served as guards for the Kohenim back in the day (which was about 3,000 years ago). It was her way of saying that I belonged more to her than to my mother’s parents. She clarified these historical matters regarding the matter of the Kohenim by tossing a few well-chosen words of classical Hebrew here and there in the way immodest persons with airs speak broken French to a long-lost family member returning from Paris in order to demonstrate how cosmopolitan they really are. For unlike Miriam and Aaron, who dressed in matching blue and pink pantsuits, and delicately smoked menthol cigarettes, Ida and Gustave had achieved higher status for being unmistakenly Eastern European, clad in decades-old black and grey garb they themselves tailored and barely uttering a word of even-broken English.

They were the pious Jews, touched, it seemed, by a divine spark, the noble ones who zey habn gegloybt in got, believed in God, unlike the slackers Lenny and Aaron, who golfed and drank and smoked and played Pinochle and mocked (to Miriam’s discontent) all the dark suits and time-honored and time-worn dour attitudes of the Russian “old farts.” My mother’s side, truth-be-told, was a bit on the “old school” side of things, which is putting the matter rather lightly, praying dutifully three times a day at the local Schul in Yiddish-inflected Hebrew, and keeping a strictly Kosher kitchen, one set of dishes for meat, another for milk, and yet another for Passover. They refused to speak much English, stubbornly living as if they had never really left the alt velt of the dirt poor villages they had actually fled away from to escape the bloodthirsty pogroms where their kind was killed for sport.

The frum menschen, or religious folk, acted friendly enough to the goyishe yids, Christian-acting Jews, on my father’s side, but they smirked in condescension when it seemed no one was looking, especially when Aaron told Gustave, each time we all got together, which was every Sunday, “if I had your money, boy would I live it up,” suggesting a preference for the life of the body and of the passions, to which Gustave replied with a sly smirk, knowing his counterpart knew nothing of the mother tongue, “but you don’t, you idiot, because ir farbrengen es aoyf khorz, [you spend it on whores],” suggesting his preference for the life of the mind and of his god. He dearly loved money, but only when it was not spent.

My father tried to buck my slow-but-steady gravitation towards my mother’s parents’ spiritual and intellectual orbit, which he saw as putting the traits of my effeminacy into the light of day more than was necessary. Previously, I had preferred his folks, the more earthy and modern grandparents in their Huckapoo shirts, who lavished us with expensive gifts they could in no way afford, such as walkie talkies, GI Joes and colorful match box cars, and all the Crayola crayons money could buy. Meanwhile, grave Ida and Gustave deplored the ethos associated with such purchases as narrishkeit, utter foolishness, and gave us only a few nickels “for College.” My father encouraged us to mock these nickels, and to lend them to him for cigarettes, which he never paid back, and instead to pay rapt attention to his father’s magic tricks, which seemed to make these same nickles disappear in one room and then reappear supernaturally in another room! As time progressed, I discovered Aaron’s secret magic book hiding in a cushion of the Lawson-style couch (on which we were not allowed to sit) that mathematically detailed how the tricks were masterminded through a variety of deliberate steps that were meant to fool the foolish.

I also began to see that the more old-fashioned couple cared intimately more about my expanding mind, and were, in their own patient way, over the course of many years, studying its contours, as if my brain were a part of their special science experiment. They bought me several gorgeously published and expensive black-and-white bible books for children, to see what supernatural effect the potent images might have on me. Their glossy thick pages revealed dozens of spectacularly handsome bible stars, especially that all-time favorite of mine, King David, looking virile, masculine, and bare-chested—and wearing a linen ephod while dancing and singing Psalms, the tehilim. And what about that half-naked picture of Jacob wrestling with the masculine Angel all night long? Or David lounging about on a 10th Century BCE divan with Jonathan in matching white blouses, with this caption: “The soul of Jonathan was knit to the soul of David and Jonathan loved him as himself.”

My Eastern European grandparents adored watching me raptly turn the pages of plush picture Bible books they bought for me, hoping I could plant a flag on their religious world—which was comprised solely of harsh Hebraic judgement and warm Yiddish jokes—rather than my father’s alcoholic and athletic sassy sexiness. So they decided to egg on my already hard-core bookish interests, grilling me whenever I came to visit, which was like every day: “Why did Abraham almost kill Isaac?” “What was Samson’s failing?” “What writing did Daniel see on the wall?” They even asked me, “Whom did David love?” to which I enthusiastically answered, “Jonathan.” The rapidity with which I answered that last so-called “trick” question made them virtually pee-in-their-pants with giggles, guffawing to each other not in Yiddish but the more secret Russian, curious that I left out Bathsheba, because, good for me, as she was, after all, a bitch and a shikse, the yiddish word for a non-Jewish woman—same thing! So they had no choice but to delightfully reward me with smelly kisses and honeyed handfuls of warm challah, as they groomed me to be their little spawn of Satan, so un-American. Their Rosemary’s Baby like glee over my interest in their morbidly Orthodox way of life only made me only want to sit and study more, especially when they regaled me with pictures of Joseph in a scintillating rainbow coat looking seductively right at the besotted reader with his comely azure eyes. Little did they know they were cultivating not Jewish affiliation but homosexual ardor!

A zey shayn, Ida boasted to anyone within earshot, about how pretty I was when alighting upon these images, adding that I possessed a yiddishe kopf, which is to say, a Jewish mentation, the highest of honors to be conferred upon a person in those days. I had been transplanted from the realm of Miriam and Aaron to the world of the Tanakh, Mishnah, Gemara, Kabbalah, books upon books upon books upon books that had kept the universe of Jewry alive for nearly 2000 since the tragic fall of the Second Temple in 70 CE to the Babylonians and which they feared would be lost without me. But what allowed for a devouring of these myths was not my love of scripture, but rather my love for the physical form of King David and Joseph in his robe of many colors.

Leonard watched this affiliation to endless boy-watching being passed of as book-reading with impatient disdain as Ida sat for hours on end with me in her roach-infested Gerard Avenue apartment near the elevated train patiently teaching me the Hebrew alphabet in the thin blue child’s basic learner’s prayer book I brought home from the Adath Israel Hebrew School. At some point, hearing me dutifully rehearse the Hebrew ABCs along with the funny dots underneath the letters that stood for vowelsone too many times, he put his coarse letter-carrier’s foot down, muttering goddamsovabitchjesuschrisalmighty. \Worse, when he found out that I was being kicked and punched regularly by a circle of street kids for being skinny and shy, he tossed the blue prayer book to the shag carpeting and dragged me downstairs to teach me how to fist fight. He yelled at me: “no you hammer head, don’t stick your thumbs inside your palms—cover your face—duck—right hand jabs—left hand protects—aim for the nose—hit hard—BAM!—don’t cry.” He succeeded in teaching me how to defend myself during those dangerous days, while also making me into a racist like him. “I’ll toughen you up, Dougie Wuggie.” To test me, for several days on end, he spied on me from behind a building as the gang proceeded to circle me threateningly to make sure I didn’t flee from the terrifying challenge.

Knowing I could never return home had I not rewarded my dad for his lessons, I ended up decking one tough-acting black kid so hard smack in his face that I shocked myself with the realization of my own violence. The kid ran crying home like a baby with rivulets of blood spouting from his nose and mouth. My father ran out of from his hiding place giddy like a school girl, wrapping me in his arms, murmuring, “I am proud of you, Doug-the-Wug.” Upon our return home, this Kowalsky-wannabe stood like an ace coach, parading me in front of the entire extended family, showing off my swollen hand, now stained with another boy’s blood and spit, to my mother’s tears and stunned horror. Ida and Gustave dropped their heads in shame, as if they had lost a small parcel of remaining land to the Czar, and I too had become a Cossack.

My father, now having me more on this side of the equator, now regaled me with long-lost heretofore unspoken tales that were actually not “lost” at all about how he had enlisted to fight the “lousy Krauts” in WWII; how he helped to build mud roads as an engineer not far from the death camps; how he and his seasoned buddies slept on the rocky ground hearing the artillery in the distance watching the passing clouds cover the moonlight in Eastern France and Western Germany —the Ardennes-Alsace Campaign; how they managed their contagious fear by playing poker, chewing tobacco, talking about dames. He reminisced while putting his fisherman’s hand around my thin shoulder, mistaking me for one of his war buddies, then abruptly ceasing such delicious affection only to push me aside, and glare at me coldly, as if I were a strange and weird boy from a distant planet who had cast a spell on him that compelled him to open up about his past.

Things were getting stressful at this time because the blurry boundary that separated the desperately poor and neglected people of the South Bronx from our idyllic home in the Central (and more white) Bronx of the Roosevelt Gardens had all but vanished into thin air. The Roosevelt Gardens kept the children safe from traffic and the cars zooming up and down the Grand Concourse. Sequestered in our courtyard area sculpted like Italian gardens, I thought we lived in suburbia. But my parents noticed that more and more drugs and riff-raff had entered the Gardens, and that the beautiful black and Puerto Rican boys I lusted after were not nearly as appreciated by my parents as they were by me. So, as resentful agents of “white flight,” we moved many miles north to Co-Op City in the North Bronx in 1971, when I was 11 years old, the largest cooperative housing development in the world at the time, and the ugliest, built as it was on a swamp with shoddy construction and through corrupt management, on what used to be an amusement park.

There were 25 high-rise buildings each 24 or 33 stories high, divided into five huge sections, 15 houses of worship, several schools and shopping centers, with each street named after a notable historical personality. (We lived on Alcott Place). The whole family followed to flee the coop of the South Bronx and move to the “Coop,” which was pronounced like the “coop” in chicken coop, including my aunt and her hippie children. Eventually Ida came to this lonely hell-hole too following Gustave’s death the year before my Bar Mitzvah, toward which he had been looking forward so much.

My father positively hated Co-Op City and begged my mother instead to buy a house in Bayside, Queens, where he could toughen us kids up by teaching us to shoot hoops in that backyard forever eluding us. There he could have built Balsa model planes and sniff the fumes from the airplane glue aptly called “dope.” But she was frightened to make such an ambitious and costly move; she could not part from her close sisters and ever-present mother who, as she grew older, required help and constant translation in doing her kosher shopping and so forth. My father did everything he could to return to the “real” Bronx. He missed his hobby and fisherman stores, and he drove us often to the once-grand boulevards to buy delicacies only found there, such as salted cashew nuts and heated onion bialys. Once, when he drove me to a classy sporting goods store on Fordham Road, another blue collar man in the same kind of Ford my father drove cut us off, almost causing a collision. My father flung his agile body out of the car, throwing himself onto the other tough guy, hollering from the top of his tar-coated lungs, “yah louse, yah almost killed my kid.” A bloody brawl ensued; a crowd gathered cheering the men on; I heard sirens. I started screaming at the top of my 11-year-old lungs, “stop, stop, please stop!” My father yelled back, “you’re embarrassing me” and “you’re screaming like a fairy.” So consumed with his humiliation by me, he missed seeing the man’s jab coming towards his face, and received a bloody nose and black eye. The man received a bloody lip and what must have been a broken rib when my father revenged the assault with full fury. I received black-and-blue bruises on my left arm, and two black eyes, because I fainted from high-pitched anxiety and crashed my face hard on the concrete. So humiliated by the horror of my screams, my father did not talk to me for six months afterwards. And we lived in a small apartment, and had to pass one another in a narrow corridor many times a day, doing so in bitter silence that no one could mediate.

To my utter heartache, my father grew to openly prefer my younger brother, who was a born athlete and had the “right friends.” They were the “bad boys” who made sardonic fun of the uptight teachers in class, composing farting songs with their hands underneath their sweaty armpits, which drove my mother into sleepless nights of worry, but brought guilty smiles to my father. My father more than once put his hand around a sinewy Puerto Rican basketball player my brother called his best friend, and on whom I had an intoxicating crush, and said, “Call me Lenny,” correcting the more formal appellation of “Mr. Sadownick,” or even “Len,” only to add in a conspiratorial whisper, “I wish you were my eldest.” How could he be unaware I was hearing this all? Once while drunk on Seagram’s Seven, and upon hearing me proclaim that I was now a vegetarian, this ethnic Willy Loman forced me to shovel steak and potatoes into my face, which I then proceeded to puke out in front of all the appalled relatives. I later on heard my parents scream at each other in their bedroom that night, the first time I had heard their decibels quite so high; she bitterly accusing him of torturing me; he morbidly accusing her of making me into “a momma’s boy.” I believe he threw something at her and she eventually begged him tearfully not to hurt her and please not to leave. My brother and I slept in one bed that night and hugged each other in tears and shivers, horrified at the screeches we had somehow not heard so clearly before.

This father of mine had every intention of winning this civil war to make me “into a man,” considering that I was studying to be Bar Mitzvahed, which is a Jewish boy’s formal entry into being a member of the community, a big deal for any Jewish lad, and a project that consumed my ardent studies for years. “If you are going to be a Bar Mitzvah,” my father groused, “you have to be a mensch,” a statement of utter hypocrisy that virtually resulted in a roll of my eyes, but I thought better of sarcasm in relation to my father. Instead of rehearsing the Hebrew melodies for hours on end, I was forced to join Little League and sport a vomit-green uniform on which I felt more than once compelled to throw up, especially when the heathen gods of summer did not look kindly about my wretched playing skills and deprived my poor soul of rain for much of the torturous summer. “He will be so proud of you,” my mother said, obviously disbelieving herself. As a matter of fact, I routinely humiliated my father, regularly dropping the few balls I managed to catch. Every game ended in unnecessary humiliation and tears held back, with me biting my lips till they bled to keep myself from crying while he turned his back on me and bitterly smoked his cigarette. A different father might have comforted me in his caring arms as I sobbed a bit. Instead, after each three-hour game sweltering in the suffocating heat of Van Cortland Park, we drove home in our cheapie 1965 Ford in ruthlessly raw silence.

The shunning ultimately devolved into naked estrangement, and things grew even worse. A year before my much-anticipated 13th Mitzvah, I suffered a crushing fall during a game of tackle football. Eight boys piled onto my torso, crushing one of my hips into a pile of ice, concrete, dog shit and slush. What at first seemed like a minor sprain evolved into an agonizing and chronic limp that led to a total breakdown of my still-growing hip-ball-and-socket organization.